MI 450 Classmates & Instructor (Feedback Only)

Reimaging

The Zoo Visitor Experience

An innovative tool to enrich the zoo experience for visitors.

Who I Worked With

My Role

UX Research

UI Design

UX Writing

Research Methods

Contextual Inquiry

Secondary Research

Competitive Analysis

Moderated Usability Testing

Evaluation Testing

Tools Used

Adobe Photoshop

UXPin

The Challenge

Creating a Tool to Increase Zoo Favorability Among Visitors

The role of modern zoos is conservation, education, research, and entertainment. More people visit zoos and aquariums each year than all the sporting events in the United States combined.

According to the Association of Zoo & Aquariums, the public's favorability on animals in zoos has decreased in the past several years while the opposition has remained stable. Without visitors, zoos cannot fulfill their mission(s).

To satisfy visitors, these facilities need to understand their visitor needs, expectations, hopes, and aspirations surrounding their zoo visit. Not only are zoo visitors more receptive to the zoo’s educational message(s) if they have a positive experience, but these experiences also influence future behavior(s) of visitors. How might we create a positive, enjoyable experience for zoo visitors?

This capstone project was developed for Michigan State University's MI 450: Human-Centered Technology Course.

Design Process

Discovery

Secondary Research

What Do We Already Know?

To kick off the project, I referenced scientific literature that has been published on the topic. I discovered that limited research has been conducted about zoo visitors outside the realm of education and learning.

Which Animals Do Visitors Prefer?

Moss and Esson (2010) studied visitor interest in 40 zoo species at the Chester Zoo, the most visited zoo in the United Kingdom. They found that the most predictive indicator of visitor interest in a particular animal was the animal's taxonomic group. Visitors are most interested in mammals and least interested in birds. Other predictors of visitor interest included animal activity, body size (length), and whether the animal was a flagship species (Moss & Esson, 2010). Their findings of visitor interest in animal activity further supported my interview data.

Moss, A., & Esson, M. (2010). Visitor interest in zoo animals and the implications for collections planning and zoo education programmes. Zoo Biology, 28, 1-17. DOI: 10.1002/zoo.20316

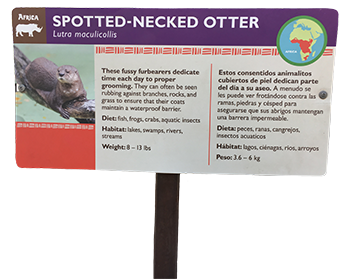

What Animal Facts Interest Visitors?

Fraser, Bicknell, Sickler, and Taylor (2009) studied what information visitors would like to know about the animals on their identification labels. Their data suggest that visitors are most interested in odd facts and behaviors, endangered animal status, and where the animal lives in the wild.

Fraser, J., Bicknell, J., Sickler, J., & Taylor, A. (2009). What information do zoo & aquarium visitors want on animal identification labels. Journal of Interpretation Research, 14 (2), 7-19.

Contextual Inquiry & Zoo Visitor Interviews

A Deep Dive into Zoo Visits

To ensure the project was grounded in real user needs, desk research was supplemented with contextual inquiry, observing zoo visitors in their natural environment. I recruited a diverse group of individuals who had recently visited zoos to:

- Understand the challenges they faced during their zoo visits.

- Gain insights into their motivations, expectations, and aspirations for future zoo experiences.

In addition to conducting interviews, I also observed visitors' behavior during their time at the zoo, noting pain points and patterns in their interactions with exhibits and services. These contextual observations helped provide a deeper understanding of their needs and how they engaged with the space.

Due to tight time constraints, I was only able to interview and observe a small group of zoo visitors, but the insights gained were invaluable in shaping the direction of the project.

Emerging Themes From Visitors

Visitors Plan Their Visit Upon Arrival

Visitors want to know the general layout of the zoo and how to navigate to the exhibits of interest.

Navigating the Zoo is a Major Challenge

The ease at which visitors can navigate the zoo impacts their overall visitor experience.

Visitors Want to Move Through the Zoo at Their Own Pace

Visitors want to wander off and do their own thing, see what they want to see, and not hold anyone up.

Visitors Want to Know What Animals They Can See

Visitors want to know what animals will be available for viewing before they begin their visit.

Visitors Want to See Animals When They are Active

Most zoo visitors do not understand animal behavior, so they cannot accurately predict the best times to view their favorite animals at the zoo.

Poor Animal Visibility Negatively Impacts Their Visit

Poor animal visibility (e.g., hidden animals, crowded exhibits, etc.) negatively impacts the visitor's experience at the zoo. Viewing animals isn't just a challenge for adults, but also for children.

Ideation

Sketching

Brainstorming Solutions

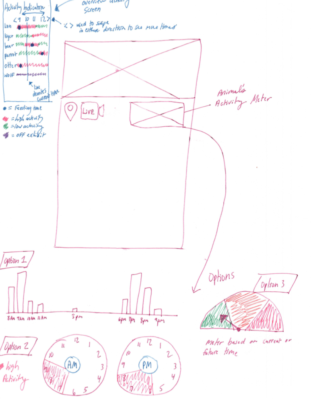

Based on user data, I generated over 50 design ideas, using sketching as a primary tool for brainstorming, exploring, and communicating concepts. Sketching proved to be an effective and efficient method, as it allowed me to quickly visualize ideas, iterate rapidly, and keep the process low-cost. The range of ideas included everything from robotic animals to mobile app features. Of the concepts developed through brainstorming, approximately 10 were successfully integrated into the final design solution.

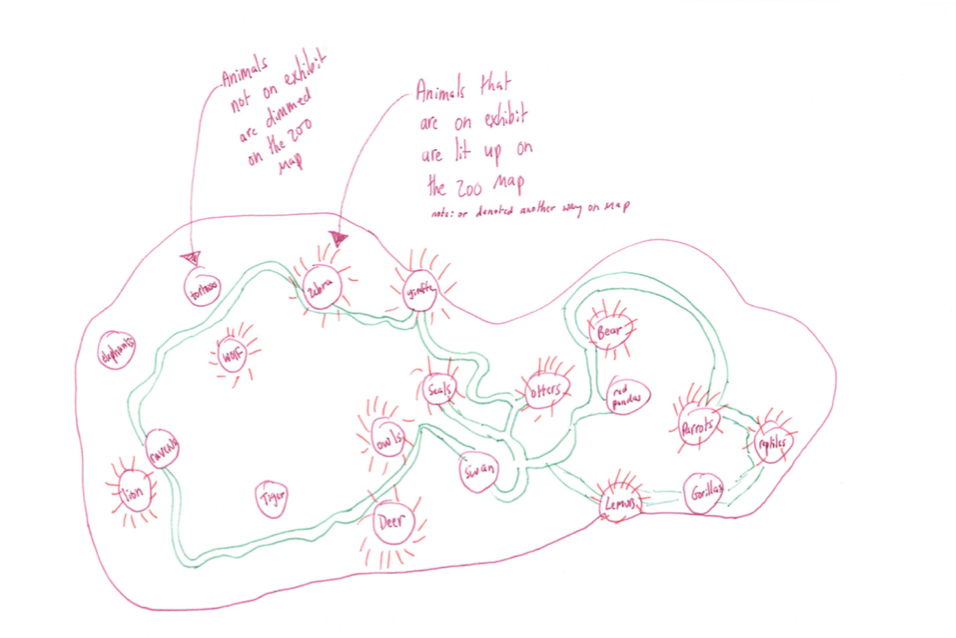

Animal Off Exhibit Map: Zoo visitors want to know whether an animal is available for viewing before walking to the exhibit. This information could be overlaid on a map to assist visitors in planning their visit.

Animal Activity: A meter displaying an animal’s typical activity throughout the day can help visitors plan their visit.

Competitive Analysis

What Are Current Zoos Apps Like?

To get a better understanding of the zoo apps currently on the market, I conducted a competitive analysis. The nine zoos included in the competitive analysis included a mix of large and small zoos that have an app for their facility. The features compared across apps were based on user data and potential design ideas for this project. A representative sample of the competitive analysis is below.

| Features | Bronx Zoo | Denver Zoo | Greenville Zoo | San Diego Zoo | Zoo Miami |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Map | Interactive | Interactive | Interactive | Interactive | |

| Navigation | |||||

| Schedule | |||||

| Best Viewing Time | |||||

| Animal Information | |||||

| Access Animal Info From Map | |||||

| Submit Questions | |||||

| Live Video Feed | Giraffes | ||||

| Animals Off Exhibit | |||||

| Set Reminders | |||||

| Call Security | |||||

| Search |

The competitive analysis revealed several key trends and insights about zoo apps:

- Common Features: Most zoo apps included basic animal information and a zoo map, though additional features varied across apps.

- Map Usability: Several maps were difficult to navigate (e.g., in PDF format), and in most cases, animal information was not easily accessible. Animal details were typically organized by taxonomy, which was not always intuitive for users.

- Content Limitations: With the exception of the Adelaide Zoo, most apps only featured animal images rather than more detailed content or multimedia.

- User Research: The Bronx Zoo was the only institution in the analysis that incorporated user experience research into the development of its app. Their straightforward design included an interactive map, exhibit distances, and closed exhibit alerts.

Overall, I discovered that many of my design ideas were not available in current products on the market – especially collectively in one app.

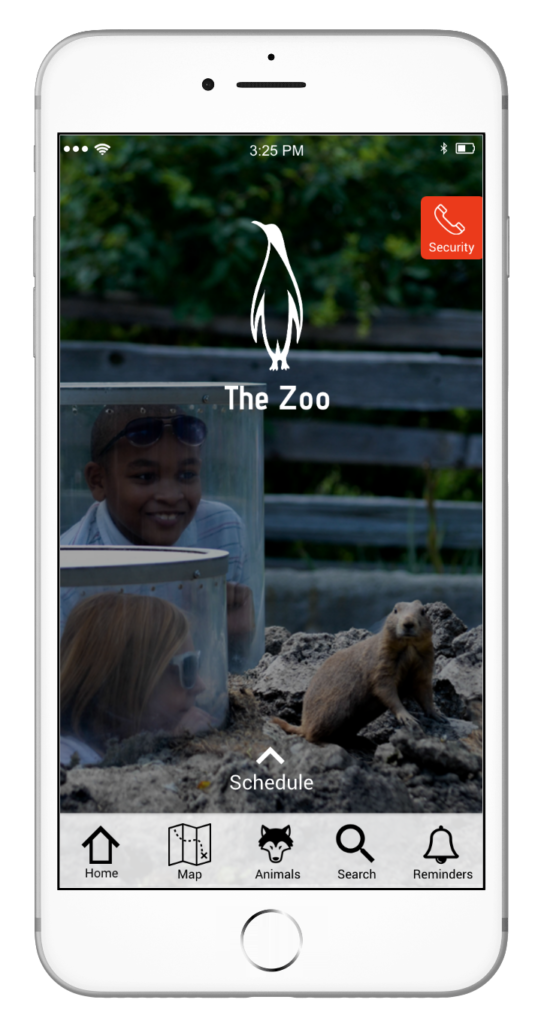

Why Chose a Mobile App?

- My research confirmed that visitors were already using their phones at the zoo.

- It was requested by real users.

- Easy to update.

- An app supports green initiatives.

- The flexibility and capabilities of an app could address many of the challenges, needs, and wishes of zoo visitors.

Design & Testing

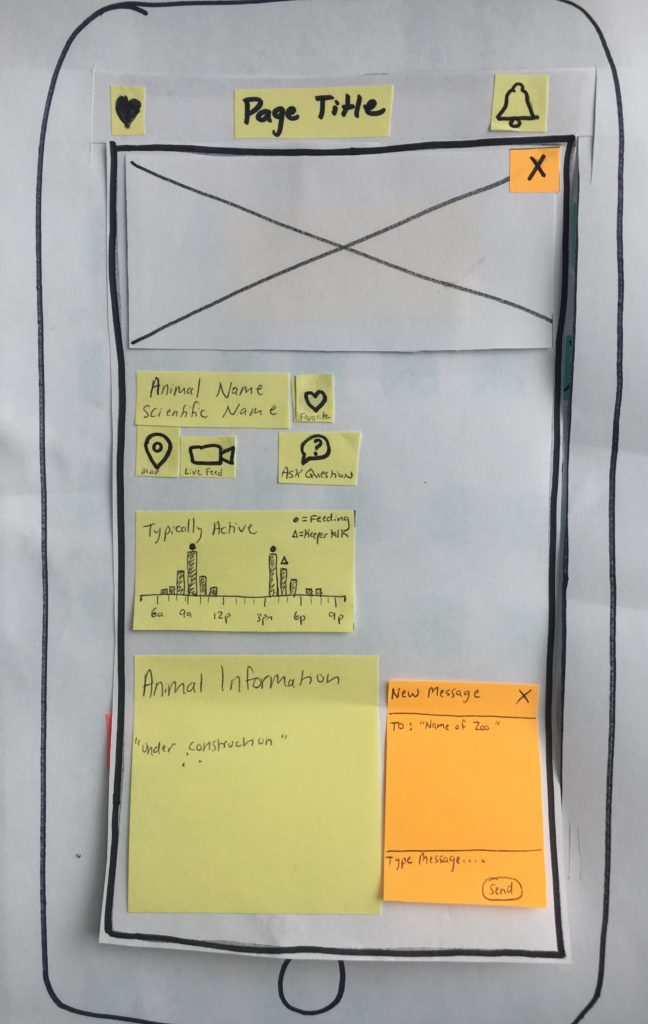

Paper Prototype & Testing

Working Out Design Ideas

I began designing the app with a paper prototype. A paper prototype was a quick, inexpensive way to test out ideas and determine requirements. Once the paper prototype was finished, I conducted usability testing with zoo visitors. Many of the behaviors and comments made by participants during the usability testing reiterated the key insights gleaned from interviews during the discovery phase.

Data from usability testing confirmed I needed to simplify the app while adding additional enhancements to select features. For example, each person loved the idea of being able to set reminders, but they wanted more contextual information provided.

The user feedback from the paper prototype usability testing was incorporated into the next iteration of the prototype.

High Fidelity Prototypes & Testing

Refining & Digitizing Designs

I created an animated, high-fidelity prototype with UXPin, a user interface and prototyping tool. The app’s design evolved and improved with each prototype iteration because of user feedback. Each phase of moderated usability testing generated new ideas and refined current concepts, getting me one step closer to a final product.

Design Iterations

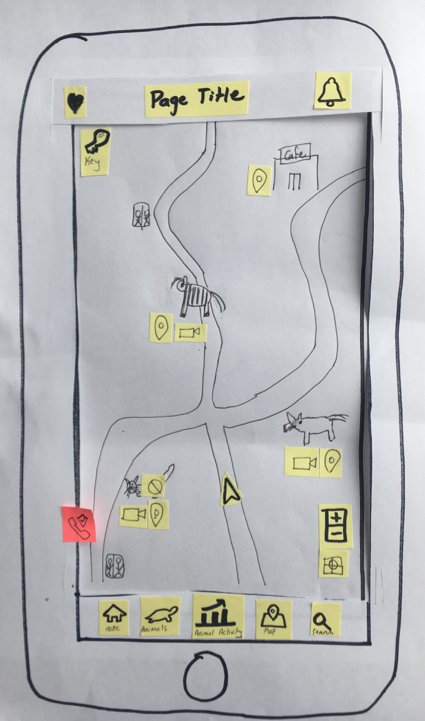

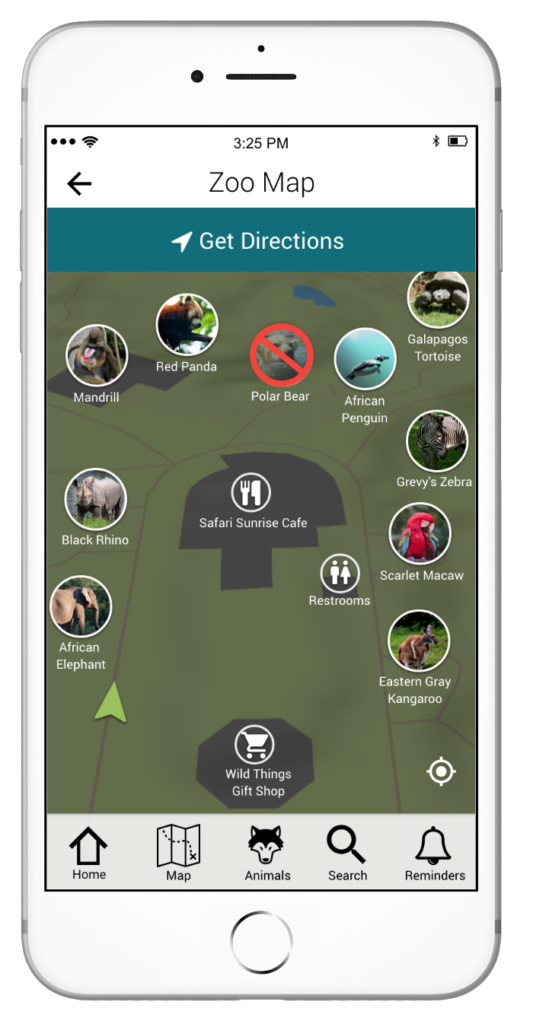

Paper Prototype

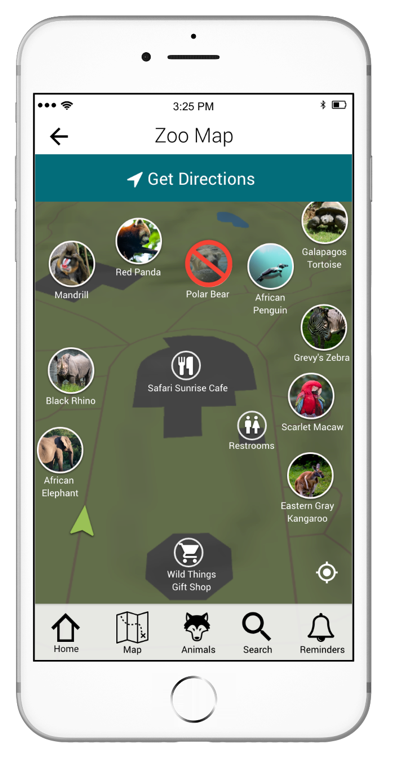

Usability testing data confirmed that I needed to simplify the map. The map was too cluttered with icons, the icon choices were confusing to users, and users did not use the map key. Users primarily accessed the individual animal pages directly from the map, so that feature was kept in the map design.

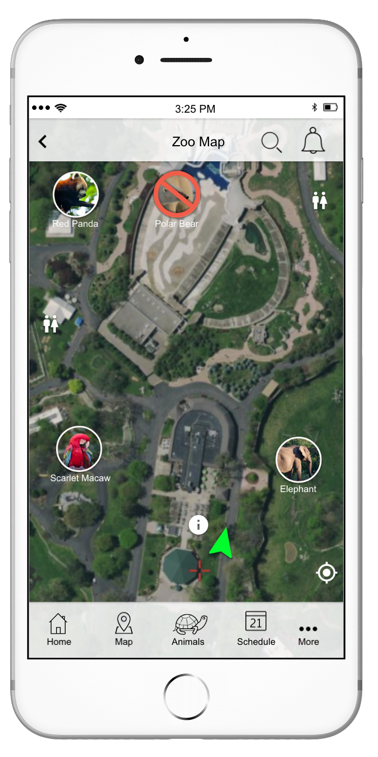

High Fidelity Prototype 1

I created an animated, high-fidelity prototype with UXPin. The prototype was presented to five users for feedback.

Based on the feedback from my higher fidelity prototype, I cleaned up the design, changed the color palette, and incorporated consistent design elements across the app.

During usability testing, users mentioned that the icons on the map were difficult to see. This problem was fixed in the next prototype by removing the satellite imagery.

At the beginning of the project, it was unclear whether users wanted turn-by-turn navigation in the app. This feature was suggested during multiple iterations of usability testing, so I decided to incorporate the feature into the next prototype iteration.

High Fidelity Prototype 2

I presented my revised prototype to five users for feedback. User feedback from the usability testing did not warrant additional changes, so this design was used for evaluation testing.

Final Product

The final design incorporated minor design changes to fix problems that arose during evaluation testing.

During evaluation testing, I discovered that there was a problem with the salience of 'get directions' on the map. This feature remained unnoticed even after viewing the map multiple times. Based on user feedback, the size of the ‘get directions’ text was increased on the map and coupled with a navigation icon used elsewhere in the app.

Evaluation Testing

Formal Testing & Finetuning App

This formal evaluation of the app was a combination of (1) users completing think-aloud scenarios with the high-fidelity prototype and (2) post-test questions. The data collected from the evaluation was used to guide design decisions to improve the ease of use and user satisfaction with the app. All evaluation testing was conducted in controlled settings.

Evaluation testing participants were from a broad age demographic (i.e., 20s-60s). All of the participants had previously visited zoos, but none had ever used a zoo app.

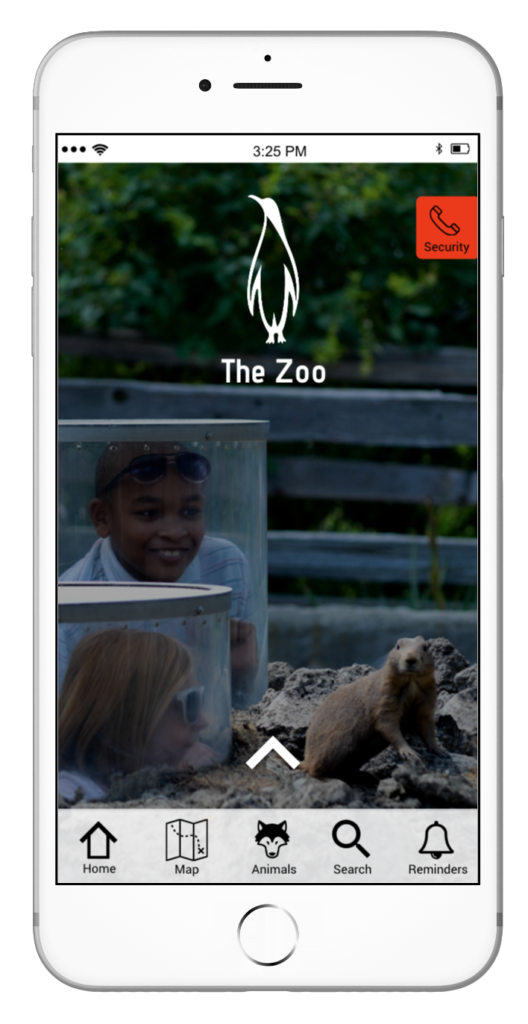

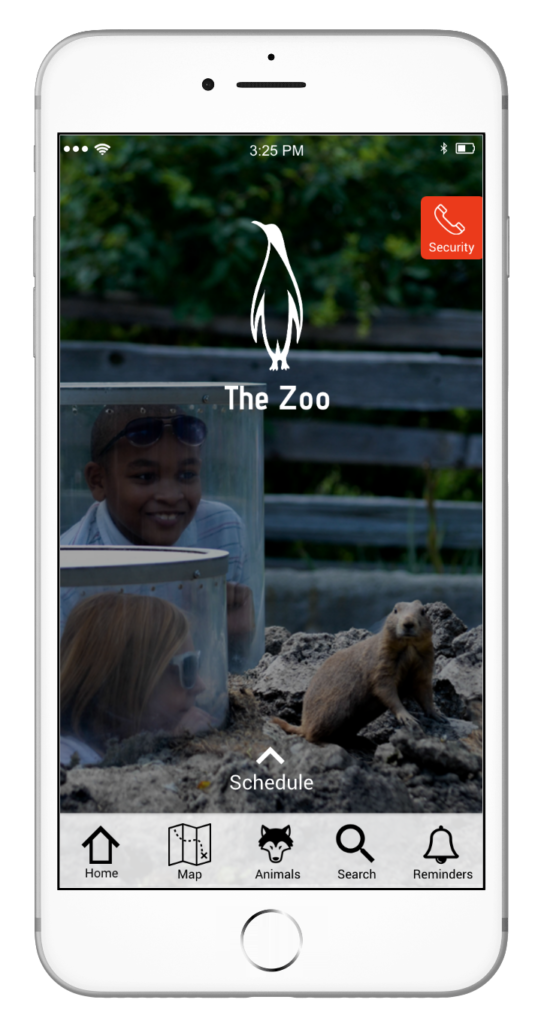

Finding 1. Swipe Up Arrow was Not Intuitive

The key problem identified was that all the participants struggled with the swipe up arrow. Consequently, they had difficulty finding information to complete several of the scenarios.

All users recommended adding text labels next to the swipe up arrows to give users a clue as to what additional information they can access. This change was incorporated into the final prototype.

before

After

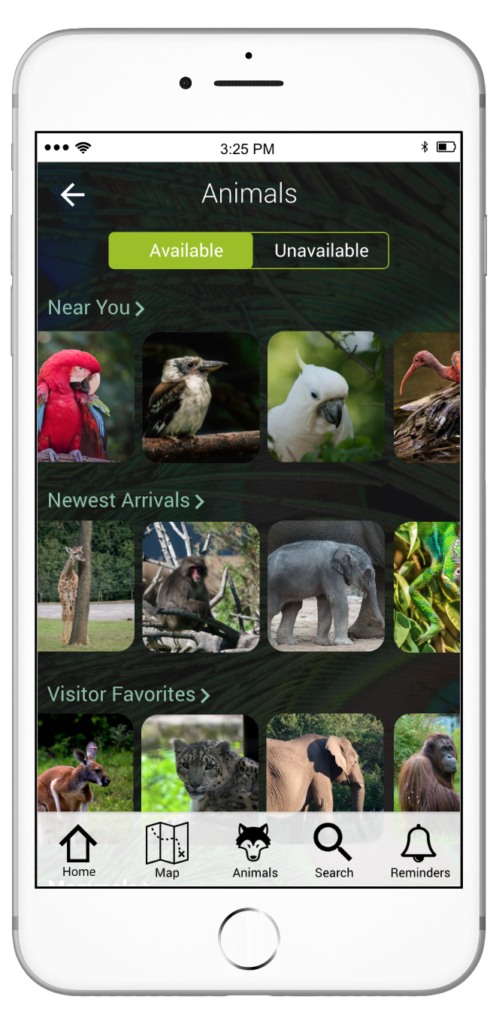

Finding 2. Increase Salience of Several Features

Another app issue that arose was the salience of several interfaces, such as the toggle on the animal page. Only minor design changes were needed to make these features more salient in the prototype. For example, the color of the available/unavailable toggle on the animal page was changed to an accessible, higher contrast color.

before

After

Finding 3. App Exceeded Evaluation Criterions

Success was based on whether each respective scenario could be completed by 70% of all participants. All the scenarios were completed with a completion rate of 75% or higher with minimal errors. Based on the criterions set in the evaluation plan, the data suggest that the evaluation of the zoo visitor app was a success. Only slight modifications were needed to improve the ease of use and user satisfaction.

Following the evaluation, I conducted a heuristics assessment. The app passed all ten heuristics.

Finding 4. Overall User Feedback Was Positive

The app received glowing feedback about its key features and usability. For example, one participant commented, "It’s appealing, easy to use. I like how you’ve streamlined it. It has so much in there but yet it’s not overwhelming.” Another person mentioned, “I am really impressed by it. I think that it looks really good and that it’s all really intuitive.”

All participants really liked the app’s features (e.g., reminders) and the app’s built-in redundancy so that they could accomplish their goal in numerous ways. In fact, one participant said, “I like the multi-faceted approach to it…there are different ways you can customize it to yourself. I think that is really nice.”

When asked at the beginning if they had ever used a zoo app, none of the users seemed particularly enthusiastic about using a zoo app. By the end of the testing, each expressed interest in using the app during their zoo visits (i.e., at the zoo itself, not prior to their visit).

Final Product

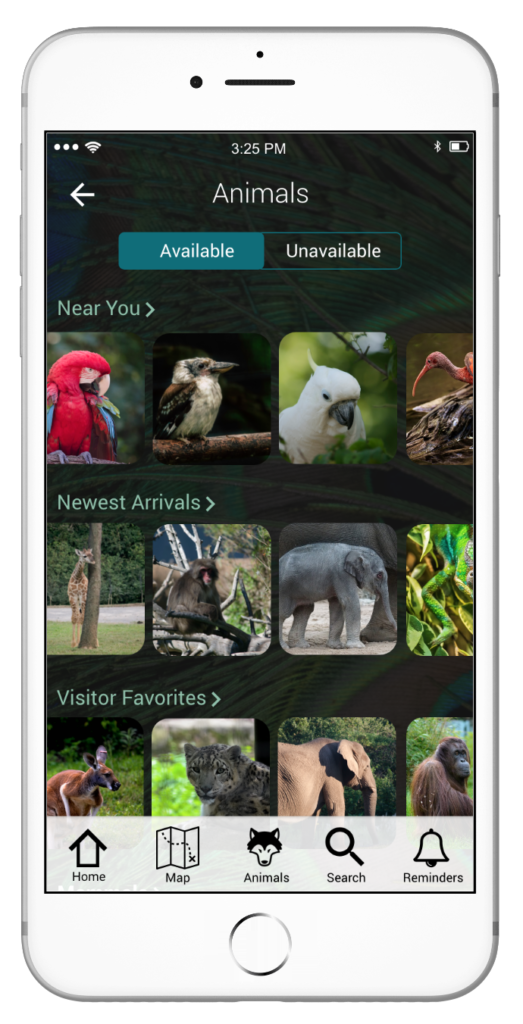

App Key Features

Feature 1. Interactive Map & Navigation

Navigating the zoo is one of the visitor’s biggest challenges they face during their visit. Benefits of a digital map include:

- Is available from anywhere in the zoo

- Cannot be lost

- Can be updated regularly

- Can help visitors navigate from point A to point B

The map was designed so visitors can quickly and easily access high priority information (e.g., turn-by-turn navigation, animal information) directly from the map.

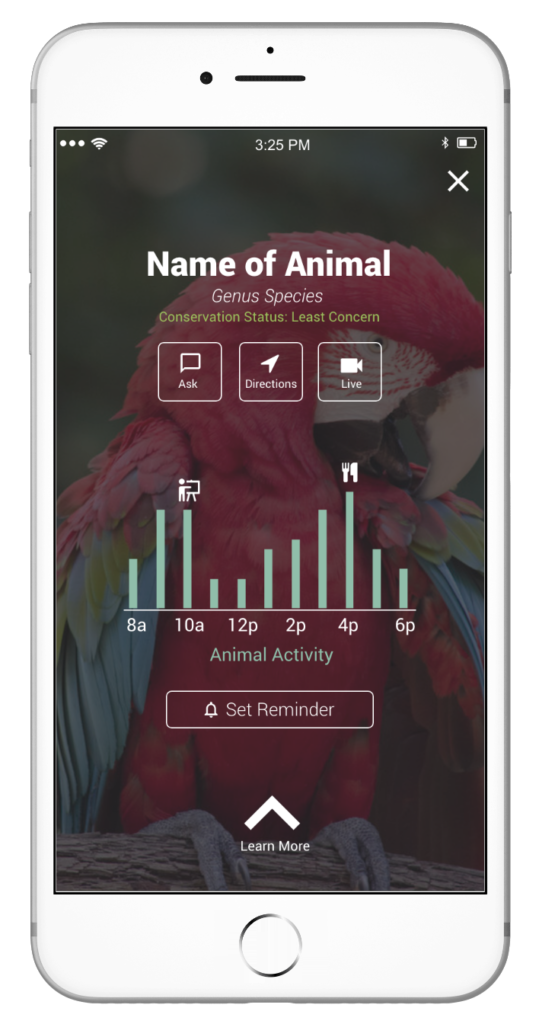

Feature 2. Animal Activity Graph

Visitors are more interested in viewing animals when the animals are active and doing entertaining behaviors. Since the typical zoo visitor does not understand animal behavior, they cannot accurately predict the best times to view their favorite animals at the zoo. If visitors knew the tigers typically play in the morning and then sleep during the afternoons, they may intentionally visit the tiger exhibit in the morning. The app includes an activity graph for each species, which indicates the animal's typical activity levels throughout the day. The graph can be used to help visitors plan when to visit exhibits of interest.

Feature 3. Live Video Feed

Visitors want to see the animals during their zoo visit. The app includes a live video feed to improve animal visibility for visitors. The video feed(s) provide alternate ways for visitors to view inside an exhibit, see an animal when it's hiding, etc.

Feature 4. Set Reminders

During the discovery phase, a user commented that she regularly checks the time on her phone at the zoo so she doesn't miss the scheduled zoo activities (e.g., keeper talks) she wants to attend. This inspired the Set Reminders Feature.

This feature allows users to set a tactile and sound alarm for:

- An activity on the zoo schedule

- When to visit a specific animal exhibit

Users can customize how far in advance they want to be notified. To help with logistical planning, the app shows users the estimated walking time from both their current location and the furthest exhibit from their final destination.

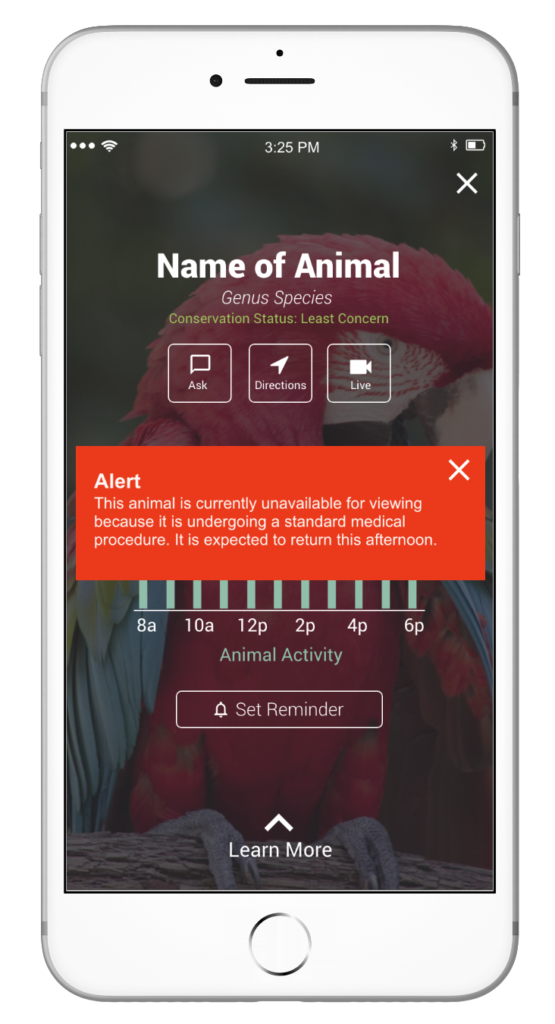

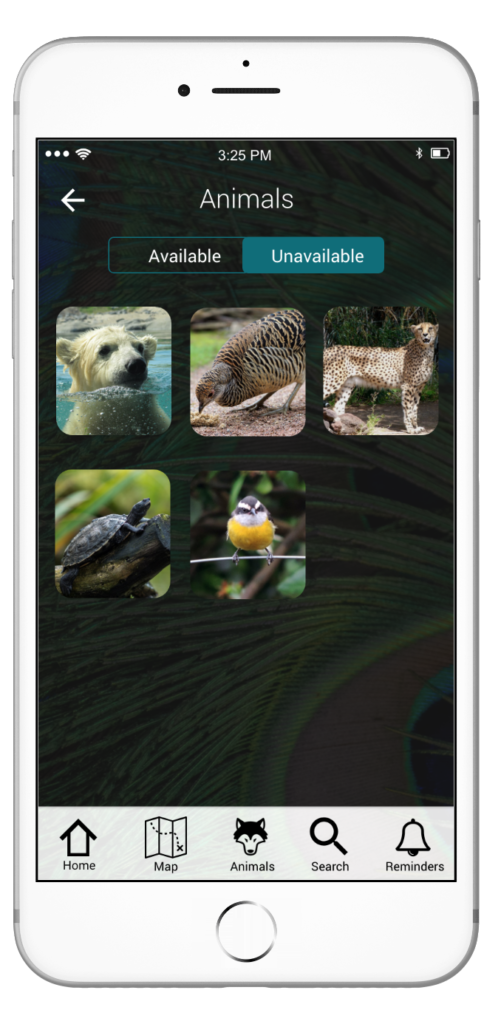

Feature 5. Animals Unavailable for Viewing Redundancy

Visitors arrive at the zoo expecting to see certain animals. Participants wished they could have a list of which animals are off-exhibit (and why) before they are immersed in their visit. Having this information upfront could help the visitors plan a more enjoyable visit. Not only would it decrease emotional disappointment and abate challenging child management situations, but also help visitors save some steps.

The app clearly denotes, in three different ways, which animals are currently unavailable for viewing. The redundancy was intentional to help users access this critical information no matter how they use the app.

Option 1

Option 2

Option 3

Conclusion

The zoo app developed for this capstone project offers many new features compared to competitors on the market. These features were developed based on data and feedback collected from real zoo visitors. The data suggest that what visitors want and what zoos think visitors need are not necessarily aligned. By listening to user needs, I was able to create a strong, usable product.

Feedback

Overall, feedback about this new zoo visitor app was very positive from all users. In fact, one usability testing participant even said, “I wish it was real.” Prior to this study, none of the participants (i.e., zoo visitors) I spoke with had ever used a zoo app. One participant had commented, “I have never used a zoo app. I’ve never even thought about one.” By the end of each evaluation testing session, users expressed interest in using the app during their zoo visit(s). One participant said, “When you first talked about this, I really couldn’t foresee me using one very often. I could see myself using this at every zoo I go to.”

Next Steps

This project was a pilot study. Due to time constraints, only a very small, representative sample of zoo visitors were interviewed at the beginning of the study. The data collected from these participants were used as inspiration for design. A more formal data analysis is needed to tease out additional insights.

Numerous design ideas and potential enhancements arose during evaluation testing. Particularly exciting ideas were to (1) link events and scheduled reminders to the map, (2) incorporate alternate modes of transportation into navigation, and (3) visitor activity graphs at individual exhibits. This could be a potential solution to solve the crowded exhibits problem idenitifed during the research phase.