Dr. Brandon F. Greene (Advisor)

Liz Schroedl (Secondary Data Collector)

Ty Gimmy (Secondary Data Collector)

Sunny Greene (Secondary Data Collector)

Colleen Hill (Secondary Data Collector)

Bolstering

Customer Horseback Riding Skills

A new tool to quickly make horseback riding safer for beginners at a trail riding stable.

Who I Worked With

My Role

Lead Researcher

Research Planning & Execution

Data Collection & Analysis

Videography

Behavior Change Design

Project Management

Research Methods

Ethnography

A/B Testing

Descriptive Statistics

Inferential Statistics

Tools Used

iMovie

Paper & Pencil

Microsoft Excel

SPSS

The Challenge

Quickly Teach Beginners How To Safely Ride a Horse

Recreational horse-related activities have evolved into a booming industry, with trail riding particularly popular in the United States. Trail riding offers a chance to enjoy the outdoors and relieve stress, while not requiring the rider to be physically fit.

Rental stables, such as Giant City Stables in Illinois, are especially popular among inexperienced riders. Here, riders pay for a horse rental, rather than a riding lesson. Although most rental stables are appropriate for beginner riders (Pavia, 2005), there is no guarantee that riders will be taught basic riding skills.

Although horseback riding carries risks, with injuries ranging from minor to severe, many incidents are preventable. To ensure a safer and more enjoyable experience, trail riders should know the basics of how to ride and operate a horse before embarking down the trail.

Design Process

Discovery

Stakeholder Interviews

Understanding the Business

I began this project by talking with stakeholders to:

- Understand business goals and challenges

- Gain insights about business processes, policies, and customer expectations

By speaking with stakeholders, I learned that:

- Trail rides were typically booked in advance, but pre-booking was not required

- Customers were asked to arrive 30 minutes prior to scheduled ride time(s)

- All customers were required to sign a release form prior to riding

- A maximum of 8-10 customers could participate in a trail ride at one time

- All trail rides were led by at least one stable wrangler

- Efficient and low-cost solutions were necessary

- Paid staff had busy workloads, with minimal extra time in their day

Surveys

Gauging Customer Riding Skills

Upon arrival at the stables, customers were asked to complete a short survey to assess their competency in horseback riding. Data confirmed that a majority of customers were beginner riders with less than 10 hours of prior horseback riding experience.

Ethnography

Observing Business Processes and Customers in Action

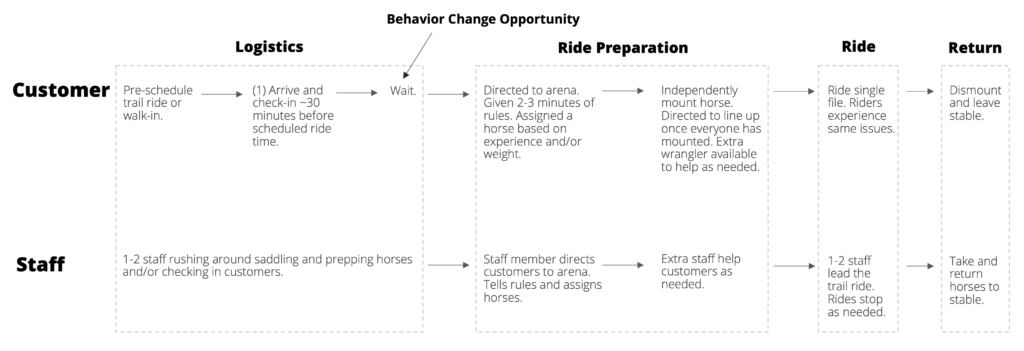

I conducted multiple, all-day ethnographic research sessions at the stable to better understand the full scope of business workflows from open until close, the business-customer dynamics, and customer needs. I was also looking for recurring challenges and potential design opportunities.

Concerns & Noteable Observations

- Once clients checked in, they sat around waiting until the trial ride was ready to begin.

- When the entire riding group had congregated near the arena, the manager of the stable gave a brief explanation (~3 minute) of how to get on a horse, steer, and mandatory rules to follow. The instruction provided wasn't consistent across trail rides.

- No teaching demonstrations were provided.

- Customers were welcome to ask questions but none did during observations.

- Horses were assigned to riders based on their weight and/or riding experience.

- Multiple customers experienced similar challenges with a particular horse(s).

- Customers were required to ride single file down the trails.

I conducted multiple, all-day ethnographic research sessions at the stable to better understand the full scope of business workflows from open until close, the business-customer dynamics, and customer needs. I was also looking for recurring challenges and potential design opportunities.

Concerns & Noteable Observations

- Once clients checked in, they sat around waiting until the trial ride was ready to begin.

- When the entire riding group had congregated near the arena, the manager of the stable gave a brief explanation (~3 minute) of how to get on a horse, steer, and mandatory rules to follow. The instruction provided wasn't consistent across trail rides.

- No teaching demonstrations were provided.

- Customers were welcome to ask questions but none did during observations.

- Horses were assigned to riders based on their weight and/or riding experience.

- Multiple customers experienced similar challenges with a particular horse(s).

- Customers were required to ride single file down the trails.

Intervention Design

What Behaviors Need to Change?

Identifying Target Behaviors

The project's goal was to improve beginner's horseback riding and safety knowledge. To pinpoint the target behaviors of interest, I consulted the authoritative literature and tapped into the expertise of the stable owner, who had more than 20 years of experience with horses. From this research, we identified and prioritized four key behaviors essential for a successful riding experience:

- Mounting

- Steering

- Riding

- Dismounting

By focusing on these foundational skills, we could help new riders build confidence and enjoy their time in the saddle safely.

Constraints & Brainstorming

Exploring Potential Solutions

During the Discovery Research, two key shortfalls emerged:

- Psychological Capability Shortfall: Customers often lack knowledge of how to safely ride a horse

- Physical Opportunity Shortfall: Many customers haven't ridden a horse before

Using the ethnography data, I pinpointed customer wait time after check-in as a behavior change opportunity.

Based on data collected during discovery and known business constraints, the behavior change design solution needed to be:

- Quick and easy to implement

- Compatible with existing stable spaces

- A cheap, low-cost solution

- Require minimal staff effort

- Acceptable to the owner

- Effective and sustainable

Literature Review: Potential Interventions

What Existing Knowledge Could Inform the Intervention?

When designing a behavior change intervention, it's crucial to start with a review of existing scientific literature, to ensure the approach is grounded in proven effectiveness. My desk research revealed a surprising gap: there were few empirical studies specifically addressing the adoption of horse safety practices, teaching horseback riding skills, or trail riding.

To broaden my understanding, I explored findings from athletics and other high-risk activities, seeking insights that could inform the intervention.

Virtual Rider Safety Program

The University of Kentucky Healthcare sponsored a five-year Saddle Up Safely Rider Safety Program aimed at educating riders on horse handling safety and reducing horse-related injuries. The program featured an interactive website with safety quizzes, tips, blogs, expert advice, and brochures. However, the program's effectiveness was not directly assessed.

Safety Training with Video?

One way to convey safety education is through video.

Numerous commercially available options can be found on platforms like Amazon, covering topics such as boating skills, stranger safety, gun safety, fire safety, water safety, hunter safety, and bicycle safety.

Additionally, many safety videos have been systematically evaluated in the behavioral safety literature addressing issues like home hazards, domestic violence in the workplace, child passenger safety, proper patient lifting, and injury prevention in sports.

Virtual Rider Safety Program

The University of Kentucky Healthcare sponsored a five-year Saddle Up Safely Rider Safety Program aimed at educating riders on horse handling safety and reducing horse-related injuries. The program featured an interactive website with safety quizzes, tips, blogs, expert advice, and brochures. However, the program's effectiveness was not directly assessed.

Safety Training with Video?

Additionally, many safety videos have been systematically evaluated in the behavioral safety literature addressing issues like home hazards, domestic violence in the workplace, child passenger safety, proper patient lifting, and injury prevention in sports.

Video Modeling: a Tool for Learning?

Video technology has grown in popularity to teach or refine skills in sports and recreational activities.

A growing body of sports literature has integrated video, as a source of modeling or feedback, into athletic training. Such sports have included: basketball, climbing, football, gymnastics, lifting, skiing, tennis, softball, and volleyball.

Can You Teach Sports Safety with Video?

Horseback riding is technically considered an athletic sport. A study by Cook, Cusimano, Tator, and Chipman (2003) explored the impact of safety videos within sports. They investigated how watching "Smart Hockey," a one-hour video by ThinkFirst Canada on concussion and spinal cord injury prevention, affected 11-year-old hockey players. After viewing the video, players showed significant improvements in concussion knowledge, which persisted for three months. Additionally, they demonstrated a reduced trend in high-risk penalties, such as cross-checking and checking from behind.

This study suggests that athletic safety video content can be effectively retained and applied over the long term.

Video Modeling: a Tool for Learning?

Video technology has grown in popularity to teach or refine skills in sports and recreational activities.

A growing body of sports literature has integrated video, as a source of modeling or feedback, into athletic training. Such sports have included: basketball, climbing, football, gymnastics, lifting, skiing, tennis, softball, and volleyball.

Can You Teach Sports Safety with Video?

Horseback riding is technically considered an athletic sport. A study by Cook, Cusimano, Tator, and Chipman (2003) explored the impact of safety videos within sports. They investigated how watching “Smart Hockey,” a one-hour video by ThinkFirst Canada on concussion and spinal cord injury prevention, affected 11-year-old hockey players. After viewing the video, players showed significant improvements in concussion knowledge, which persisted for three months. Additionally, they demonstrated a reduced trend in high-risk penalties, such as cross-checking and checking from behind.

This study suggests that athletic safety video content can be effectively retained and applied over the long term.

Why Choose a Training Video Intervention?

Based on the scientific literature, video modeling is effective in teaching and/or refining athletic performance in other competitive or recreational sports, so it had potential applications for horseback riding instruction.

Benefits of developing and playing a training video at Giant Stables included:

- Make use of the time customers spent waiting.

- All customers would receive consistent training.

- Limited disruption to current employees' workflow: Just hit play.

- Low cost.

- More learning opportunities for customers.

- Could be customized to the context and specific needs of Giant City Stables customers.

- Easy to update as needed.

For safety precautions, stakeholders did not want to terminate the standard verbal instruction, so a training video would be supplemental.

Changing Behavior

Intervention Recommendation

What: Customers watch a video explaining and demonstrating essential knowledge and skills

Where: Waiting area at Giant City Stables

Who Involved: Staff member or stable volunteer

When: After check-in

How Often: Before each trail ride

Implement & Test

Task Analysis

Deconstructing Behaviors of Interest

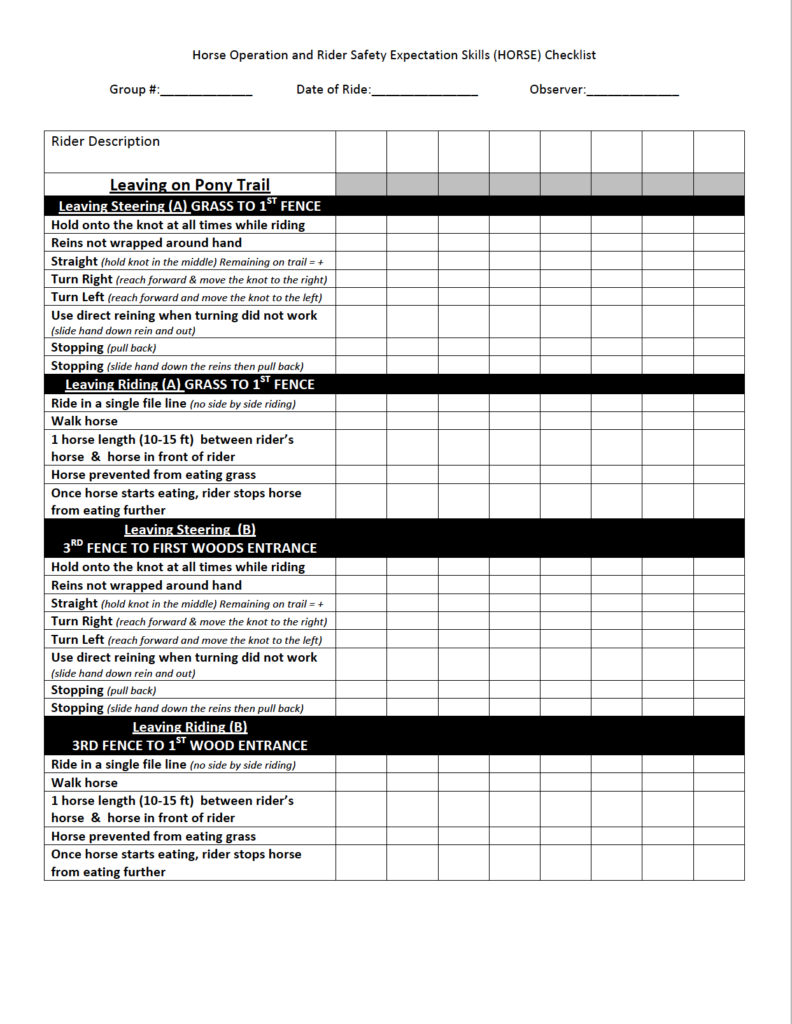

Together with the stable manager (combined 40+ years of horse experience), we developed a Horse Operation and Riding Safety Expectations (HORSE) Task Analysis. The task analysis identified step-by-step basic horse management skills within each of the four target behaviors: mounting, steering, riding, and dismounting. These steps comprised the stable’s trail riding protocol from start to finish, and would be used to teach and measure horseback riding skills.

Video Prototype

Working out Design Ideas

I created multiple script and storyboard iterations in collaboration with the stable manager. All footage was filmed on-site at Giant City Stables and edited using iMovie. The result was a 4-minute instructional video demonstrating how to mount, steer, ride on the trail, and dismount a horse.

Key behaviors, such as mounting and dismounting the horse, included step-by-step breakdowns with subtitles, while the steering segment showcased the rider's perspective for maneuvers like turning and stopping. The video aligned with the components of the HORSE task analysis, concluding with stable advertisements.

The video prototype was reviewed by stakeholders for feedback. After the video was revised to incorporate stakeholder feedback, it was field-tested with customers and further refined based on the research insights.

A/B Testing + Field Study

Field Testing & Finetuning the Video

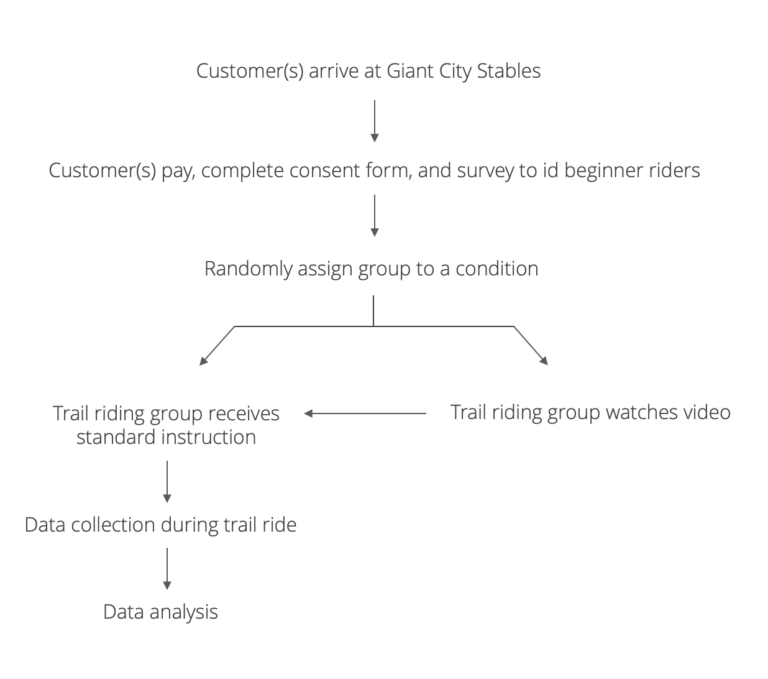

Participants

A sample was drawn from the customers who arrived for guided trail rides during business hours at Giant City Stables. Although all riders in a trail riding group received, at minimum, the standard safety instruction prior to the guided trail ride, customers who reported more than 10 hours of horse experience were excluded from data collection.

Experimental Design

This study utilized a post-test only A/B group design. Based on the liability and potential safety concerns of putting a beginner rider on a horse without any prior safety instruction, neither a pretest nor a control group was incorporated into the design.

Procedures

Customers were randomly assigned to one of two conditions without replacement, with the constraint that all riders on a given trail ride were provided the same condition:

- Standard Instruction (n = 17)

- Standard Instruction + Video Prototype (n=20) or Standard Instruction + Video Prototype Iteration 2 (n=8)

All customers were, at minimum, presented with the standard instruction offered by the stable.

Upon arrival, customers completed release forms and paid for their trail ride. They were then directed to either watch a video in the waiting area or meet by the bleachers for standard verbal instruction. Meanwhile, wranglers secured the horses in the arena and adjusted their tack. After the instruction concluded, customers were assigned horses, mounted up, and set off on their trail ride. Throughout the session, wranglers refrained from prompting riders, allowing them to attempt each step independently unless they were at risk of harm.

New Iteration: Contextual Examples Added to Video

During the field study, I noticed that customers (across both conditions) were still making mistakes and having the same recurring issues managing their horses (e.g., stopping a horse from eating grass, steering horses who veer off the trail, making a horse stand still).

To address these challenges, a second iteration of the instructional video (5 min 30 sec in length) was created which included additional footage of:

- Contextual specific examples demonstrating how to troubleshoot the additional horseback management issues identified during data collection

- Reviewed key concepts at the end of the video.

The revised video (Vr) was then used in place of the original video (V) condition during A/B field testing.

Data Collection

A maximum of five beginner riders per trail ride were assessed using the Horse Operation and Rider Safety Expectations (HORSE) Task Analysis.

Observers, positioned on foot, evaluated all mounting components in the arena, dismounting in the barnyard, and riding and steering skills at two designated checkpoints along the trail, marked by landmarks. These locations were identified as areas where riders typically faced challenges. Observers maintained a distance of at least ten feet while remaining within earshot of the horses and riders.

A second trained observer independently recorded data for 67% of the riders to ensure interobserver agreement and minimize bias. All secondary observers were current or former volunteers at Giant City Stables, familiar with stable protocols.

MEASURING EFFECTIVENESS

Finding Meaning in the Data

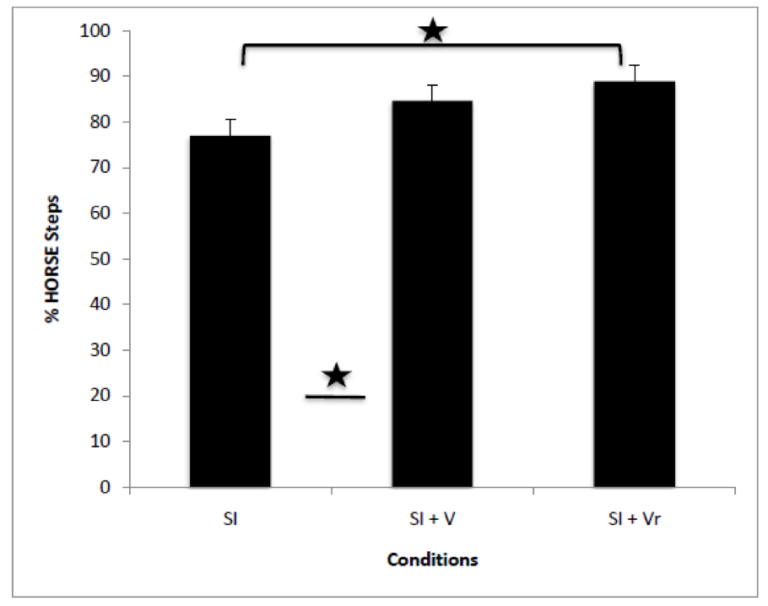

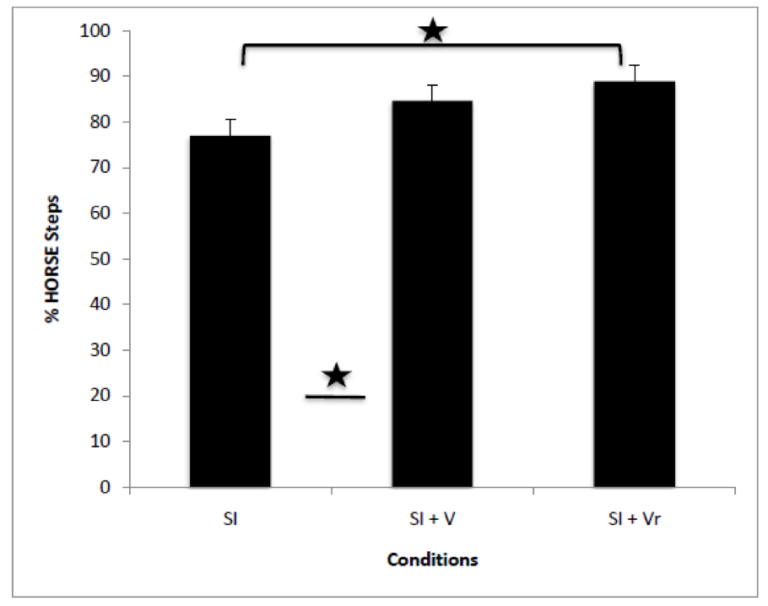

To assess how different types of instruction affected beginner riders' performance, I conducted a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests. This allowed me to compare the average percentage of task analysis steps completed correctly across three instructional conditions:

- Standard Instruction (SI)

- Standard Instruction + Video Prototype (SI + V)

- Standard Instruction + Revised Video Prototype (SI + Vr)

The analysis revealed a significant difference based on the type of instruction (F (2,42) = 6.797, p < 0.05). Specifically, riders who received only standard instruction (SI) completed significantly fewer skills independently compared to those who received the standard instruction along with either version of the instructional video (SI + V or SI + Vr). However, there were no significant differences in performance between the two video conditions. Similar trends were observed in the mounting and dismounting behaviors.

These findings highlight the value of incorporating video into training, as it enhances beginners' ability to perform essential riding skills.

A one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests were computed to compare the mean percentage of Horse Operation and Riding Safety Expectations (HORSE) task analysis components completed independently (overall and across categories) by customers who qualified for the study (i.e., beginner riders) across all three instruction conditions. The one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference for the type of instruction (F (2,42) = 6.797, p < 0.05). Consequently, Tukey’s HSD was used to determine the nature of the differences between the types of instruction.

Customers who only received the classic standard instruction (SI) completed significantly fewer overall horseback riding skills independently (m = 77.10, sd = 4.95) than customers who received standard instruction paired with the first iteration of the instructional video (V) prototype (m = 84.72, sd = 10.55) or the revised video (Vr) prototype (m = 88.96, sd = 7.18). However, there were no significant differences found in the riding skills of customers who watched either version of the instructional video. Statistical analyses found similar findings across the mounting and dismounting categories.

Horseback riding skills were evaluated with the HORSE task analysis at both the beginning and end of the trail ride. Similar to the other findings, significantly fewer riding skills were completed correctly by customers leaving on the trail ride who only received the standard verbal instruction (m = 83.76, sd = 12.01) than customers who also watched the revised instructional video (m = 97.22, sd = 5.14). The overall horseback riding skills of customers who watched the first version of the training video (V) in addition to the standard instruction was not significantly different from either of the other two instructional conditions. Similar findings were also found in the customer's steering skills. No significant differences were found in customer riding skills as they returned from their 40-minute trail ride or in the frequency of prompts given to customers by wranglers.

Conclusion

The results suggest that, for at least one horseback riding stable, a custom-designed video can serve as a quick and valuable teaching tool for beginner riders when used in combination with standard instruction.

The stable manager reported that she had observed a noticeable improvement among riders who had watched the supplementary instructional video when arriving back to the barnyard and during the dismount. Despite her initial reluctance to set aside time for the video, she now insists that all customers watch the revised instructional video prior to a trail ride.

Limitations

There were numerous methodological limitations worthy of mention:

- A pre-test was not administered to participating customers prior to instruction because of safety concerns expressed by the stable manager. Therefore, it is unknown whether there were pre-existing differences in customer beginner riding skills prior to instruction, even though all reported less than ten hours of horse experience.

- In addition, observers were not granted permission from the stable to assess rider performance throughout the forty-minute trail ride in the woods. The data collected was a sample of the rider’s skill set at the beginning and end of the trail ride.

- Finally, there may have been a sequence effect since video instruction was always presented before the standard verbal instruction. Supplemental qualitative data from customers would have also been a plus.

Next Steps

This study did not evaluate the effects of video instruction alone because of potential safety concerns. Now that A follow-up study is needed to investigate whether that practice suffices to teach the skills targeted by the Horse Operation and Rider Safety Expectations (HORSE) Task Analysis.

The project was unique not only in relevance to horse safety but in extending the use of video modeling into the recreational horse industry. It suggests that other uses of video in equestrian activities should be explored. Such applications might involve more experienced and/or competitive riders.